The need for a decimal system of units

For as long as people have counted in tens, there has been the need for a decimal system of measurement units. Non-decimal measurement units inevitably require the use of conversion factors, which increase the difficulty of carrying out even the simplest of calculations.

In contrast, the decimal metric system has no conversion factors. Instead, for most practical purposes, all that is required is to know the values of a handful of decimal prefixes, which can be used to make very large and very small values more manageable.

Compare, for example, the simple task of finding the area of a room:

| IMPERIAL | METRIC |

| 17 ft 7 in × 12 ft 11 in | 5.4 m × 3.9 m |

| = ((17 × 12) + 7) in × ((12 × 12) + 11) in | |

| = 211 in × 155 in | |

| = 32 705 in2 | |

| = (32 705 ÷ 144) ft2 | |

| = 227 17⁄144 ft2 | |

| = 227 ft2 17 in2 | = 21.06 m2 |

Length

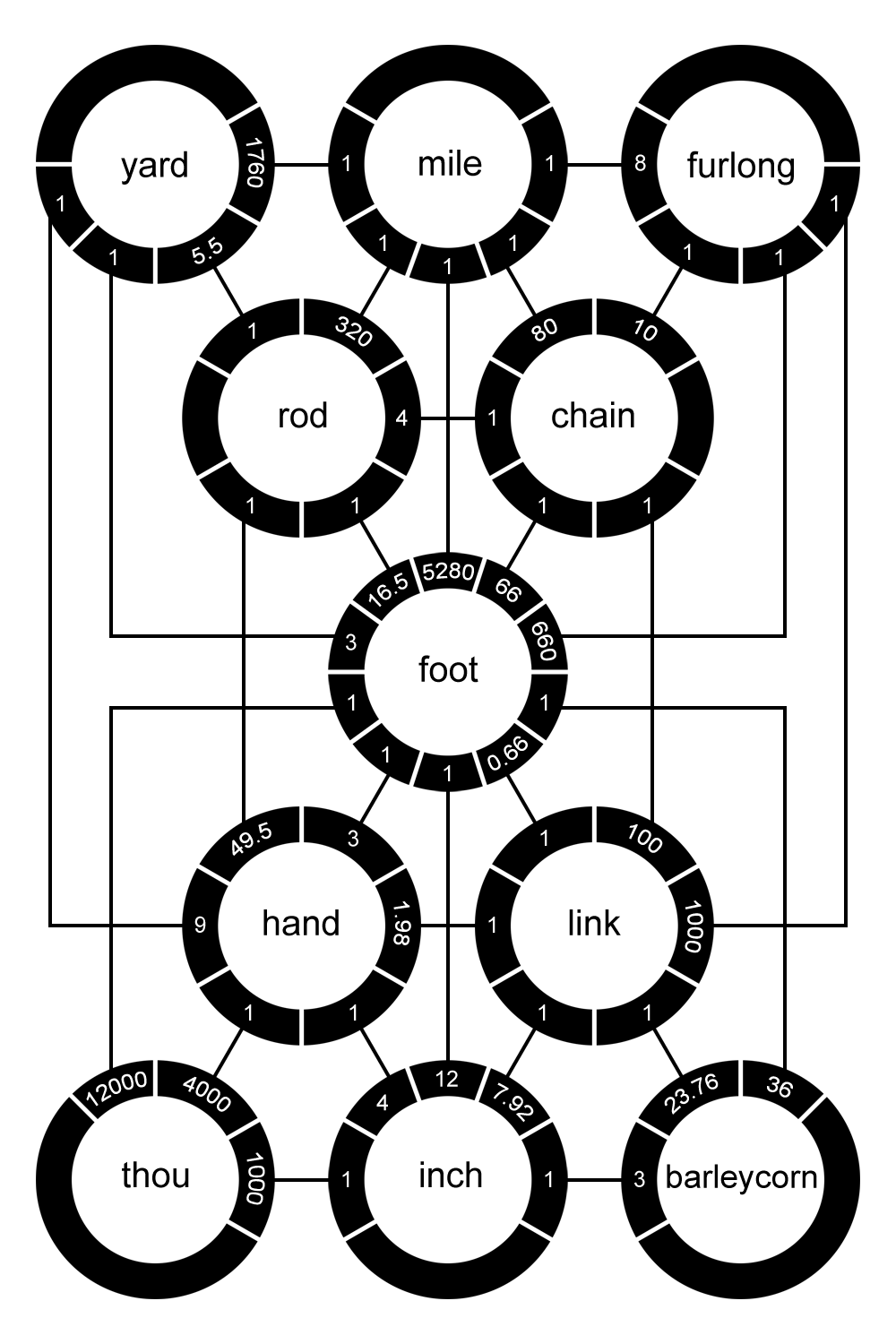

The mile, which has a random-looking definition in the imperial system, was originally a decimal unit of measurement. Its name is derived from the Latin “mille passus”, meaning “1000 paces”, where a pace was equal to two normal walking strides. The diagram below shows how the mile is related to some of the many other imperial units of length.

In 1895, a Government report stated that no less than one year’s school time would be saved if the metric system were taught instead of the complicated system of tables of imperial weights and measures in use at the time.

| IMPERIAL | METRIC |

|

|

Before the 17th century, the non-decimal nature of imperial units of length made land-surveying calculations particularly onerous.

In 1620, this issue was addressed by English mathematician Edmund Gunter. His solution involved the introduction of new decimal units of length. He decimalised the furlong by dividing it into 10 chains, of 100 links each. However, the fact that one link was equal to 7.92 inches, meant that the link remained unused outside the field of surveying.

The need for a more complete overhaul of measurement units remained, and the issue was revisited later in the 17th century.

In 1668, more than 120 years before the launch of the metric system, English natural philosopher John Wilkins proposed a universal decimal system of measurement. Published by the Royal Society, An Essay Toward a Real Character, and a Philosophical Language, included the core elements of the future metric system.

In considering how to define a standard unit of length, Wilkins dismissed suggestions of “subdividing a Degree upon the Earth” as being impractical. Instead, his proposed “Standard” unit of length, would be based on the length of a seconds pendulum – a pendulum where each swing has a duration of one second, and a period of oscillation of 2 seconds. The length of the pendulum he described equates to approximately 0.997 metres using today’s definition of the metre. Wilkins proposed the redefinition of existing measurement units in terms of decimal multiples of his “Standard” unit of length.

Let this Length therefore be called the Standard;

let one Tenth of it be called a Foot;

one Tenth of a Foot, an Inch;

one Tenth of an Inch, a Line.

And so upward,

Ten Standards should be a Pearch;

Ten Pearches, a Furlong;

Ten Furlongs, a Mile;

Ten Miles, a League, &c.

John Wilkins, An Essay Toward a Real Character, and a Philosophical Language – 1668

Wilkins’ universal decimal units of length

| Wilkins’ decimal unit | Metric equivalent | |||||

| Line | = | 1⁄1000 | Standard | millimetre | 10-3 | m |

| Inch | = | 1⁄100 | Standard | centimetre | 10-2 | m |

| Foot | = | 1⁄10 | Standard | decimetre | 10-1 | m |

| Standard | metre | m | ||||

| Pearch | = | 10 | Standards | decametre | 101 | m |

| Furlong | = | 100 | Standards | hectometre | 102 | m |

| Mile | = | 1000 | Standards | kilometre | 103 | m |

Wilkins’ new definition for the mile equates to 1000 Standards, or approximately 1000 metres, thus restoring the mile’s original Latin-derived decimal meaning of “mille”, or “thousand”.

Despite the obvious attraction of Wilkins’ universal decimal measures, his proposals were not adopted for over 120 years.

In 1819, a report by a Government commission, appointed “to consider more uniform weights and measures”, failed to recommend switching to the recently launched decimal metric system. There is also no evidence that John Wilkins’ proposals were considered by the commission at the time.

It wasn’t long before more issues emerged as a consequence of not adopting decimal measures.

By the 1850s, there was an increasing need for measurements with a precision finer than 1⁄64 in. The practical difficulties of using traditional fractions, based on successive halving, were already apparent, where even a simple task like counting was difficult using multiples of 1⁄64 in. Simple arithmetic, such as 1 5⁄64 in + 3 7⁄16 in, was also far more error-prone than the equivalent sum in millimetres. Moving to a precision of 1⁄128 in or 1⁄256 in, using traditional fractions, would probably have been unworkable.

In 1857, English engineer Joseph Whitworth addressed this issue in a paper titled, Standard Decimal Measures Of Length:

… instead of our engineers and machinists thinking in eighths, sixteenths and thirty-seconds of an inch, it is desirable that they should think and speak in tenths, hundredths, and thousandths …

Joseph Whitworth, Standard Decimal Measures Of Length – 1857

This led to the adoption of the “thou” as a de-facto decimal unit of length in engineering.

This stop-gap solution remained in place for a century, before the needs of international trade finally triggered a switch to the metric system. From the 1960s onwards, the use of the thou in UK engineering was phased out in favour of SI units. In the USA, the thou remains, although there it is sometimes referred to as the “mil”, which can be confused with the colloquial word “mill”, meaning “millimetre”.

Whilst the metric system has yet to be fully adopted on road signs, the UK’s official map system has used a kilometre-grid system since the 1940s, and the metric system as a whole has been used for practically all other official purposes since 2000.

Area

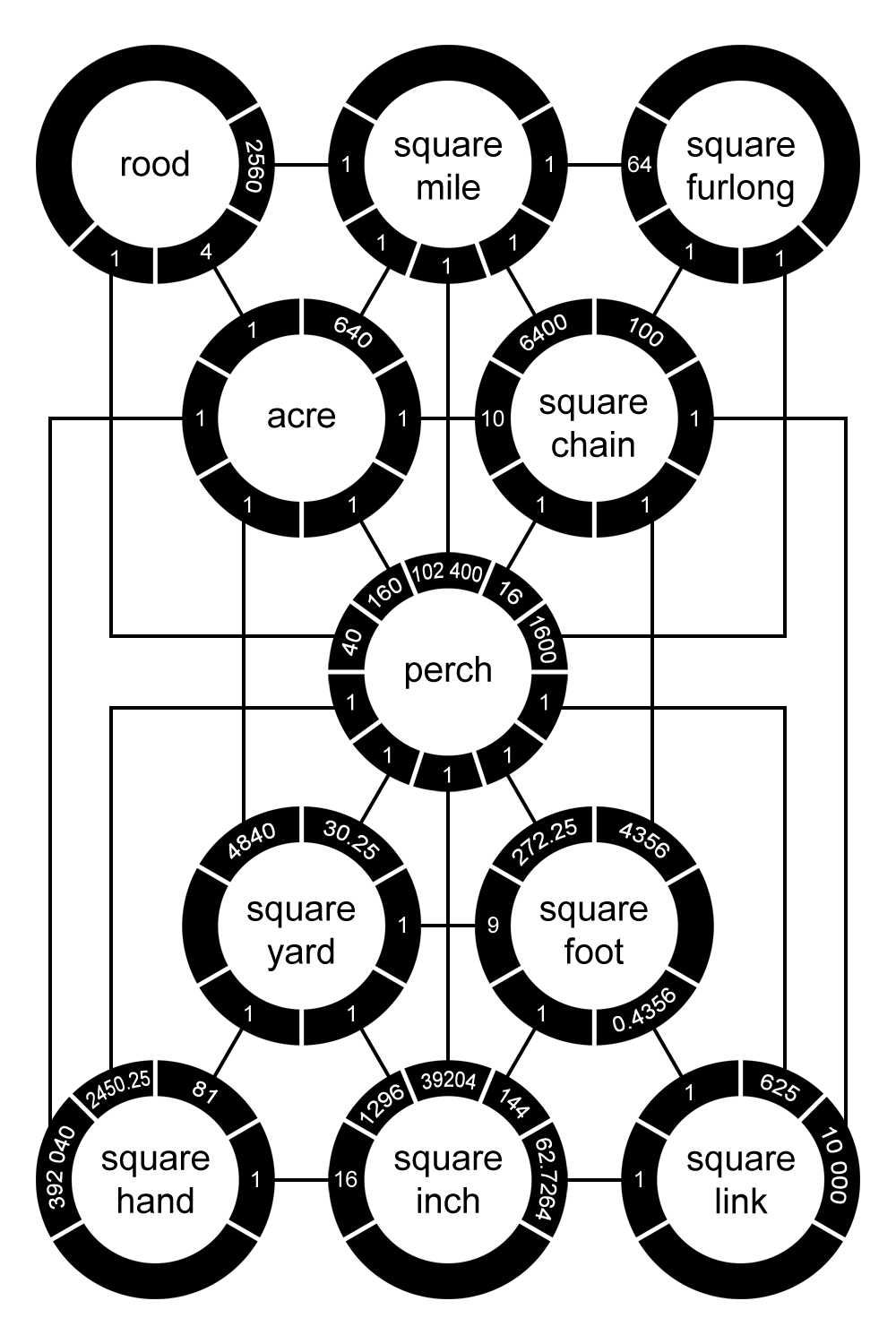

The use of imperial units of area requires another set of obscure conversion factors to be learned. Most imperial units of area are simply the square of imperial units of length. The main exception is the acre, which is equal to the area of a rectangle with a length of one furlong and a width of one chain.

| IMPERIAL | METRIC |

|

|

As can be seen from the diagram above, one acre is equal to 4840 square yards, or 43560 square feet, or 160 perches each of 30.25 square yards. The acre seems therefore to be a particularly Byzantine unit for land surveyors to be required to use as a standard unit of land area.

However, in 1620, Gunter’s use of novel decimal units of length greatly simplified the task of measuring land area in acres. By dividing a furlong into 10 chains, or 1000 links, he was able to measure a plot of land to an accuracy of one link, and calculate its area in square chains without resorting to conversion factors. The fact that 10 square chains was equal to one acre, meant that he only had to move the decimal point to know the area in acres.

The task of converting acres to square miles still required a non-decimal conversion factor of 640. Non-decimal conversion factors also remained for converting fractions of acres to the smaller units of area used in commerce at the time, such as the rood and the perch.

It wasn’t until three hundred years after John Wilkins first proposed a universal decimal measurement system, that surveying became fully-decimalised, switching to the sole use of the metric system in the 1960s.

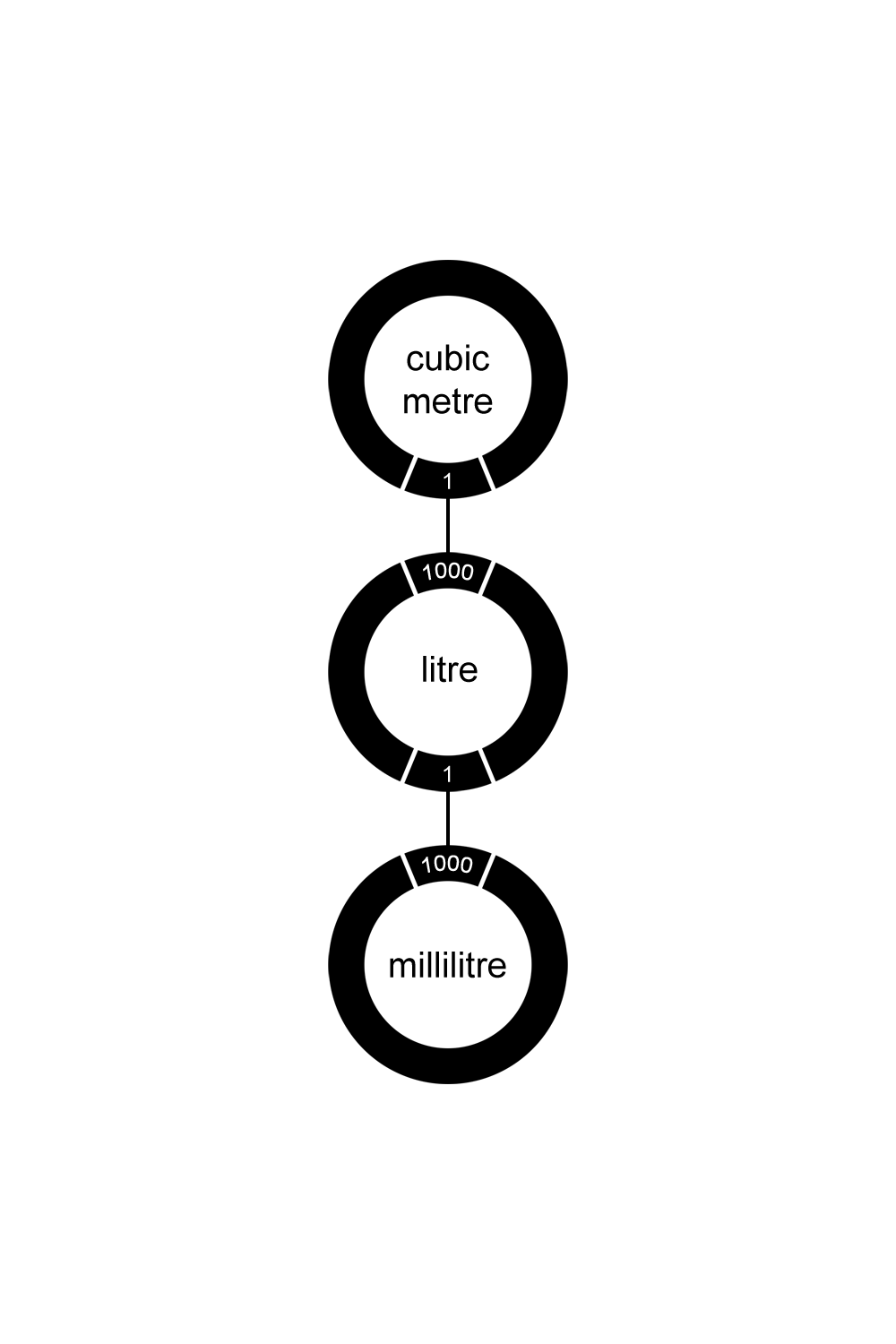

Volume

Imperial units of volume include two incompatible base unit definitions – the cubic inch, and the gallon. This creates a complex matrix of user-unfriendly conversion factors.

| IMPERIAL | METRIC |

|

|

John Wilkins’ proposals for decimal measurement units included the following for units of volume, or capacity. Again, his proposals took the names of existing imperial measurement units, and redefined them in terms of decimal multiples of a single standard unit:

And so for Measures of Capacity:

The cubical content of this Standard may be called the Bushel:

the Tenth part of the Bushel, the Peck;

the Tenth part of a Peck, a Quart;

and the Tenth of that, a Pint, &c.

John Wilkins, An Essay Toward a Real Character, and a Philosophical Language – 1668

Wilkins’ universal decimal units of volume

| Wilkins’ decimal unit | Metric equivalent | |||||

| Pint | = | 1⁄1000 | cubic Standard | litre | 10-3 | m3 |

| Quart | = | 1⁄100 | cubic Standard | decalitre | 10-2 | m3 |

| Peck | = | 1⁄10 | cubic Standard | hectolitre | 10-1 | m3 |

| Bushel | = | cubic Standard | kilolitre | m3 | ||

In Wilkins’ system, one bushel equates to approximately one cubic metre, and one pint equates to about one litre.

In 1824, there was a half-hearted attempt at decimalisation when the gallon was redefined as the volume occupied by 10 pounds of water at room temperature. This was of little practical value though, as the gallon was subdivided into 8 pints, not 10. As the switch to the metric system became inevitable, in 1963 the definitions of both the imperial gallon and cubic inch were updated in terms of exact amounts in cubic metres.

Wilkins’ proposals for decimal units of volume were finally adopted in the UK in the 20th century in the form of the modern metric system, or SI.

Mass

Imperial units of mass, or weight, consist of two intertwined systems – troy weights and avoirdupois weights. This creates an array of cumbersome conversion factors. Additionally, there was a third system of weights, the apothecaries’ system, which remained in use for prescription medicines until the 1960s.

To compound matters, before the development of the metric system, there was very little standardisation of weights and measures internationally.

The lack of a single standard unit of mass, across the international scientific community, and the lack even of a standard way for it to be subdivided, was a source of frustration for Scottish engineer James Watt, who in 1783, gave an account of his difficulties understanding the values used by scientific writers using different measurement systems.

To address these issues, Watt proposed that there should be a universal standard pound, which would consist of 10 ounces, or 10 000 grains. He also expressed his support for redefining the foot such that the mass of one cubic foot of water would be equal to exactly 1000 ounces.

Shortly afterwards, James Watt’s concerns were addressed more fully by the development of the metric system.

After the British Parliament rejected a proposal, in 1790, for the metric system to be developed jointly by France and Great Britain, France went on to develop and launch the metric system independently, with the system being formally defined in French law on 7 April 1795. The system built on the principles previously laid out by John Wilkins.

| IMPERIAL | METRIC |

|

|

In 1824, all imperial weights were defined in relation to a single brass artefact that defined the troy pound – a unit that was itself withdrawn from use for trade in 1879.

To the present day, the use of the troy ounce for trade in precious metals continues to cause misunderstandings, where a price quoted in ounces can be mistaken to be 10% higher than the actual price.

John Wilkins’ proposals for a universal decimal system of measurement are so similar to the metric system, that it can be argued that he invented the metric system. As would be the case for the subsequent definition of the kilogram in the metric system, his base unit of mass is based on the mass of water occupying a cube with edges equal to a standard unit of length.

As for Measures of Weight;

Let this cubical content of distilled Rain-water be the Hundred;

the Tenth part of that, a Stone;

the Tenth part of a Stone, a Pound;

the Tenth of a Pound, an Ounce;

the Tenth of an Ounce, a Dram;

the Tenth of a Dram, a Scruple;

the Tenth of a Scruple, a Grain, &c.And so upwards;

Ten of these cubical Measures may be called a Thousand,

and Ten of these Thousand may be called a Tun, &c.

John Wilkins, An Essay Toward a Real Character, and a Philosophical Language – 1668

Wilkins’ universal decimal units of weight (mass)

1 Hundred = Mass of one cubic Standard of water

| Wilkins’ decimal unit | Metric equivalent | ||

| Grain | gram | 10-3 | kg |

| Scruple | decagram | 10-2 | kg |

| Dram | hectogram | 10-1 | kg |

| Ounce | kilogram | kg | |

| Pound | 10 kilograms | 101 | kg |

| Stone | 100 kilograms | 102 | kg |

| Hundred | tonne | 103 | kg |

| Thousand | 10 tonnes | 104 | kg |

| Tun | 100 tonnes | 105 | kg |

Wilkins’ proposal, that the “Hundred” should be defined as being equal to the mass of one cubic standard of water, results in a “Pound” being equivalent to 10 kilograms, and an “Ounce” being equivalent to one kilogram.

If, instead of the “Hundred”, the “Tun” is defined as being equal to the mass of one cubic standard of water, Wilkins’ list of units results in equivalents that more closely resemble the magnitudes of their original imperial definitions – with a “Pound” being equivalent to 100 grams and an ounce being equivalent to 10 grams.

Wilkins’ universal decimal units of weight (mass)

1 Tun = Mass of one cubic Standard of water

| Wilkins’ decimal unit | Metric equivalent | ||

| Grain | centigram | 10-5 | kg |

| Scruple | decigram | 10-4 | kg |

| Dram | gram | 10-3 | kg |

| Ounce | decagram | 10-2 | kg |

| Pound | hectogram | 10-1 | kg |

| Stone | kilogram | kg | |

| Hundred | 10 kilograms | 101 | kg |

| Thousand | 100 kilograms | 102 | kg |

| Tun | tonne | 103 | kg |

In contrast to the imperial system, metric units of mass, or weight, for everyday use are much simpler. The only minor irregularity is the megagram, being equal to one million grams, or 1000 kilograms, which continues to go by the non-SI name of tonne.